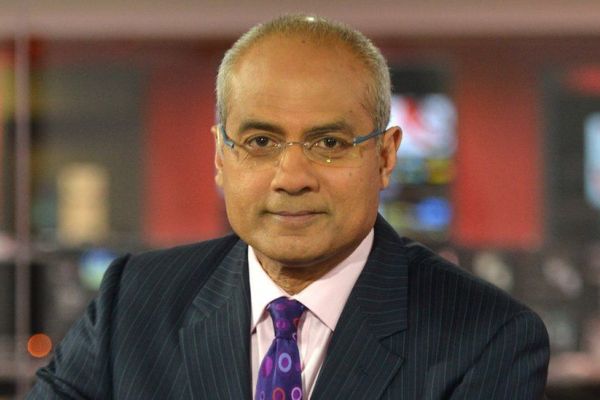

George Alagiah, one of the respected and longest-tenured journalists for the BBC, went away at the age of 67, nine years after receiving a cancer diagnosis.

In a statement issued by his representative, it was stated that he “passed away peacefully today, surrounded by his family and loved ones.”

He has been a mainstay of British television news for more than three decades and has hosted BBC News at Six for the last twenty years.

Prior to that, he was a distinguished international journalist who covered a variety of countries, including Iraq and Rwanda.

He had a stage four colon cancer diagnosis in 2014, and in October 2022 he reported that it had advanced.

Everyone who knew George loved him, whether they were friends, coworkers, or members of the general public, according to his agent Mary Greenham.

He was simply a unique human being. The woman remarked,

“My thoughts are with Fran, his sons, and his extended family.”

Although he “fought to the bitter end,” Alagiah died away early on Monday. The BBC’s director general, Tim Davie, said,

“The news about George has saddened the whole BBC. We are now thinking of his family.”

He was more than simply a great journalist; his audience could sense his sensitivity, compassion, and remarkable humanity. He was adored by everybody, and we shall all miss him dearly.

It would be challenging to find a friend or colleague who is more compassionate, kind, observant, and daring, according to John Simpson, editor-in-chief of BBC World Affairs.

He was praised by Lyse Doucet, the BBC’s senior international reporter, as a “great broadcaster,” a “kind colleague,” and a “thoughtful journalist.”

“On a personal note, George affected all of us in the newsroom with his compassion and generosity, his warmth and good humor,” said Clive Myrie, the host of BBC News at One. At BBC News, we loved him, and I loved him as a mentor, friend, and colleague.

Other reporters who paid homage were Mark Austin of Sky News, Pippa Crerar of the Guardian, and Sangita Myska of LBC.

In a tweet, Austin said,

“This is heartbreaking. A nice man who competed with him for the position of foreign reporter, but who was first and foremost a friend. If empathy is a key component of good journalism, George Alagiah possessed a lot of it.”

Myska brought up the influence Alagiah had on British Asian journalists.

“When I was a kid, my dad would say, ‘George is on!’ when George Alagiah of the BBC was on television!” We hurried to visit the writer who served as an example for British Asian writers. This scene was played out repeatedly across the UK. George, we appreciate you. RIP xx”

According to the former BBC North American editor Jon Sopel, “George was the most decent, upright, kind, and honorable guy with whom I have ever worked. Tributes will be given to a brilliant journalist and excellent broadcaster. “What a tragedy!”

When Frank Gardner, a BBC security journalist, was wounded and critically hurt in an al-Qaeda attack in Saudi Arabia in 2004, Alagiah visited him in the hospital.

We talked for hours about the region he loves and spent a large portion of his career chronicling as he gave me his book, A Passage to Africa. A brilliant writer and a true journalist.

Alagiah received recognition for his reporting on the turmoil and hunger in Somalia at the beginning of the 1990s. For his coverage of Saddam Hussein’s killing of the Kurds in northern Iraq, he was nominated for a Bafta in 1994.

He was named the year’s top journalist by Amnesty International in 1994 for his reporting on the Burundian civil war, and he was the first BBC reporter to cover the Rwandan genocide.

George Maxwell Alagiah, who was born in Colombo, Sri Lanka, first lived in Ghana and then England as a young boy.

His most vivid recollection of Sri Lanka from his youth is one of leaving. The nation, then known as Ceylon, was torn apart by racial warfare, and his parents were Christian Tamils.

Donald, his father, was a specialist engineer in irrigation and water distribution. He moved his young family to Africa in search of a better life since he didn’t feel comfortable or welcome in his own nation.

Despite the family’s early success in Ghana, Alagiah’s parents decided to send their kids to England for their academic studies. When his father left him off at the residential school in Portsmouth when he was 11 years old, they both struggled to control their emotions.

His personality was affected by change and integration during his formative years, which also influenced his professional judgment.

There was prejudice there. Being almost the only person of race, he was subjected to “Bongo Bongo land” taunts in the showers. His name is pronounced “Uller-hiya” by his family.

He remembered, “In those days, you were almost embarrassed if you had a ‘funny name’.” The other option was to stick out like a cactus in a meadow in the spring.

In some respects, however, his English school, St. John’s College, was a closed and artificial society that isolated him from the massive social changes occurring outside its walls. He was mostly unaware of the widespread anti-immigrant sentiment in many parts of the nation.

He thought that as he got older, he was the “right kind” of immigrant to a place where “class always trumps race.”

Subsequently, while studying at Durham University, he fell in love and subsequently wed Frances Robathan.

After graduating, he worked for seven years at South Magazine, which was proud of its editorial stance that portrayed an unequal world as unstable.

In 1989, he joined the BBC as a foreign correspondent and later became an African correspondent, in his home continent.

Frequently, it was a melancholy experience. He conducted interviews with juvenile combatants in Liberia and victims of mass rapes in Uganda, and he witnessed hunger and disease virtually everywhere.

“There is a new generation in Africa,” he wrote. “My generation, the children of freedom, born and educated in those years of euphoria following independence, had an opportunity. We did little with it.”

According to him, one of his greatest professional moments occurred in 1999 when he transmitted some of the first images of the ethnic cleansing in Kosovo.

In news reports and documentaries, he also covered the trade in human organs in India, street children in Brazil, the civil war in Afghanistan, and human rights violations in Ethiopia, among other topics.

Among the individuals he interviewed were South African President Nelson Mandela, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, and Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe.

He presented the BBC One O’Clock News, BBC Nine O’Clock News, and BBC Four News before becoming one of the principal presenters of the Six O’Clock News in 2003.

He anchored news broadcasts from Sri Lanka following the tsunami of December 2004, as well as from New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina and Pakistan following the South Asian earthquake of 2005.

In 2008, he was awarded an OBE for services to journalism.

“Energetic and inspired”

In 2014, following Alagiah’s initial cancer diagnosis, the disease spread to his liver and lymph nodes, necessitating chemotherapy and multiple operations, including the removal of the majority of his liver.

When he returned to presenting in 2015, he said he was “richer” for the experience and that working in the newsroom was “such an important part of staying energized and motivated.”

In January 2022, he stated that he believed the illness would “probably kill me in the end” but that he felt “extremely fortunate” despite this.

In 2022, he explained on the Desperately Seeking Wisdom podcast that it took him some time to realize what he “needed to do” when his illness was first diagnosed.

“I had to pause and say, ‘Hold on a second. If the period appeared at this moment, would my life have been a failure?’

The family I had, the opportunities my family had, the good fortune to meet [Frances Robathan], who is now my wife and companion of all these years, and the children we raised… it did not feel like a failure.

Alagiah and Frances had two offspring together.

Also Read: Juan Williams Of Fox News Quits The Five! 43 Years Married Life